The geothermal areas of Yellowstone include several geyser basins in Yellowstone National Park as well as other geothermal features such as hot springs, mud pots, and fumaroles. The number of thermal features in Yellowstone is estimated at 10,000. A study that was completed in 2011 found that a total of 1,283 geysers have erupted in Yellowstone, 465 of which are active during an average year. These are distributed among nine geyser basins, with a few geysers found in smaller thermal areas throughout the Park. The number of geysers in each geyser basin are as follows: Upper Geyser Basin (410), Midway Geyser Basin (59), Lower Geyser Basin (283), Norris Geyser Basin (193), West Thumb Geyser Basin (84), Gibbon Geyser Basin (24), Lone Star Geyser Basin (21), Shoshone Geyser Basin (107), Heart Lake Geyser Basin (69), other areas (33). Although famous large geysers like Old Faithful are part of the total, most of Yellowstone’s geysers are small, erupting to only a foot or two. The hydrothermal system that supplies the geysers with hot water sits within an ancient active caldera. Many of the thermal features in Yellowstone build up sinter, geyserite, or travertine deposits around and within them.

The various geyser basins are located where rainwater and snowmelt can percolate into the ground, get indirectly superheated by the underlying Yellowstone hotspot, and then erupt at the surface as geysers, hot springs, and fumaroles. Thus flat-bottomed valleys between ancient lava flows and glacial moraines are where most of the large geothermal areas are located. Smaller geothermal areas can be found where fault lines reach the surface, in places along the circular fracture zone around the caldera, and at the base of slopes that collect excess groundwater. Due to the Yellowstone Plateau‘s high elevation the average boiling temperature at Yellowstone’s geyser basins is 199 °F (93 °C). When properly confined and close to the surface it can periodically release some of the built-up pressure in eruptions of hot water and steam that can reach up to 390 feet (120 m) into the air (see Steamboat Geyser, the world’s tallest geyser). Water erupting from Yellowstone’s geysers is superheated above that boiling point to an average of 204 °F (95.5 °C) as it leaves the vent. The water cools significantly while airborne and is no longer scalding hot by the time it strikes the ground, nearby boardwalks, or even spectators. Because of the high temperatures of the water in the features it is important that spectators remain on the boardwalks and designated trails. Several deaths have occurred in the park as a result of falls into hot springs.

Prehistoric Native American artifacts have been found at Mammoth Hot Springs and other geothermal areas in Yellowstone. Some accounts state that the early people used hot water from the geothermal features for bathing and cooking. In the 19th century Father Pierre-Jean De Smet reported that natives he interviewed thought that geyser eruptions were “the result of combat between the infernal spirits.”[5] The Lewis and Clark Expedition traveled north of the Yellowstone area in 1806. Local natives that they came upon seldom dared to enter what we now know is the caldera because of frequent loud noises that sounded like thunder and the belief that the spirits that possessed the area did not like human intrusion into their realm. The first white man known to travel into the caldera and see the geothermal features was John Colter, who had left the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He described what he saw as “hot spring brimstone.” Beaver trapper Joseph Meek recounted in 1830 that the steam rising from the various geyser basins reminded him of smoke coming from industrial smokestacks on a cold winter morning in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In the 1850s famed trapper Jim Bridger called it “the place where Hell bubbled up.”

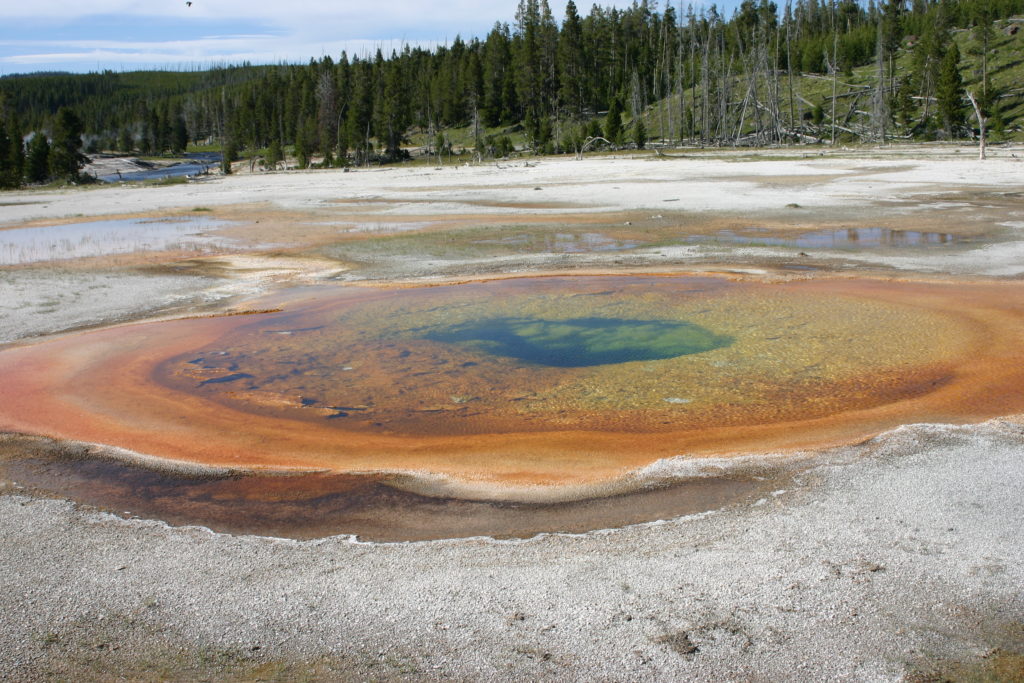

We made a family visit to Yellowstone and captured the beauty and power of the geothermal events. A gallery from the trip is posted below. Remember that all of our pictures are provided herein with permission to be copied or reproduced to support the preservation and development of natural habitat in North America.